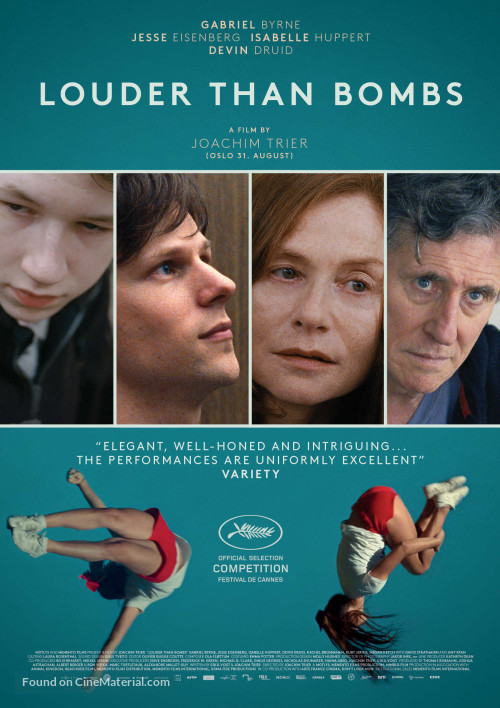

Movie Breakdown: Louder Than Bombs (Noah)

Pre-Screening Stance:

Everything I’ve seen/heard about Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier’s English-language debut seems to mark it as the type of purposefully joyless indie film often times frequented by one of its main actors, Mr. Jesse Eisenberg. Lucky, for me at least, I am fond of joyless films, regardless of the presence of Mr. Eisenberg.

Post-Screening Ramble:

Not to be too much of a pretentious fuck, but the closest thing I can compare Joachim Trier’s film, Louder Than Bombs, to is Joan Didion’s brutally, heart-wrenching memoir A Year of Magical Thinking. In that book, Didion lost both her husband and, spoiler alert, daughter in the same horrible year. In Louder Than Bombs, a trio of sensitive, intelligent male family members (Gabriel Byrne, Jesse Eisenberg, and Devin Druid) lose, in a physical sense, their mother – a famous war photographer. Grief is not a simple, linear emotional arc, as much as Hollywood tries to tell us that. And in both these texts, we are dropped into the middle of the grieving process, and instead of watching the bad stuff go away, and the good stuff get closer, it is more like experiencing a hazy cloud of memory and reflection. The audience in Trier’s film ostensibly follow a week or so in the lives of Jonah (Eisenberg), Gene (Gabriel Byrne), and Conrad (Devin Druid) – a family still speaking almost two years after their mother killed herself. This isn’t, I mean it is but it isn’t, just a weekend of healing, it’s a slow unveiling of the emotional state of each of its characters, all deeply scarred by both the death of their mother and the life that chose to live so far from them. And instead of us just watching them interact, we see their lives expand in ripples, sometimes touching, sometimes overlapping, but always rippling outwards from the grieving point. Gabriel Byrne is a joy to watch, a soft man who had lost his wife long before she died, now burdened with the all the parts of parenting he never wanted or asked for. All of the acting could be described as staid, with no one being asked to extend themselves too terribly far, but it’s a part of the picture, maybe even a part of the genre, Trier’s working with here. This is a deeply sad film, and each character (and thus actor) is so immersed in their own forms of melancholy, that even the slightest change in emotion can be identified as character progression. Trier is a very good director, but on occasion the film seems to broadcast its intent too much – this is a film about sadness, look how serious this film is – and though it never grows stiff or boring, at times it borders just on the farthest edge of manipulative. Regardless, Trier’s (and Didion’s) choice to float down from the memory cloud and spend some time here and there and everywhere in between makes for a film that gives the audience the chance to cycle backwards and forwards through the memories and emotions of the people on screen.

One Last Thought:

Jesse Eisenberg is handily the most awkward man alive. I’m always wondering if he’s going to snap and kill someone on screen or just sadly shuffle into a corner and break into tears.

I enjoyed your review very much. I particularly appreciate your call-out to Joan Didion’s great work. I agree with you: this film is much closer to her book than it is to a film to which it has been compared–Ordinary People. Love that film, but this is different territory altogether, as you note.

Appreciate also what you have to say about Gabriel Byrne’s work in this film.

You might, if I can presume for just a minute to tell you how to clarify this review, note at the beginning that 2 of these men have lost their mother and 1 of them has lost his wife, the mother of his children. It was a bit confusing at the top there. You cleared it up later, of course.

Anyway, I’m glad you appreciated the film. Not everyone does. I personally think it is brilliant and very much in line with Trier’s previous work, which you should see if you have not already.

Thank you!