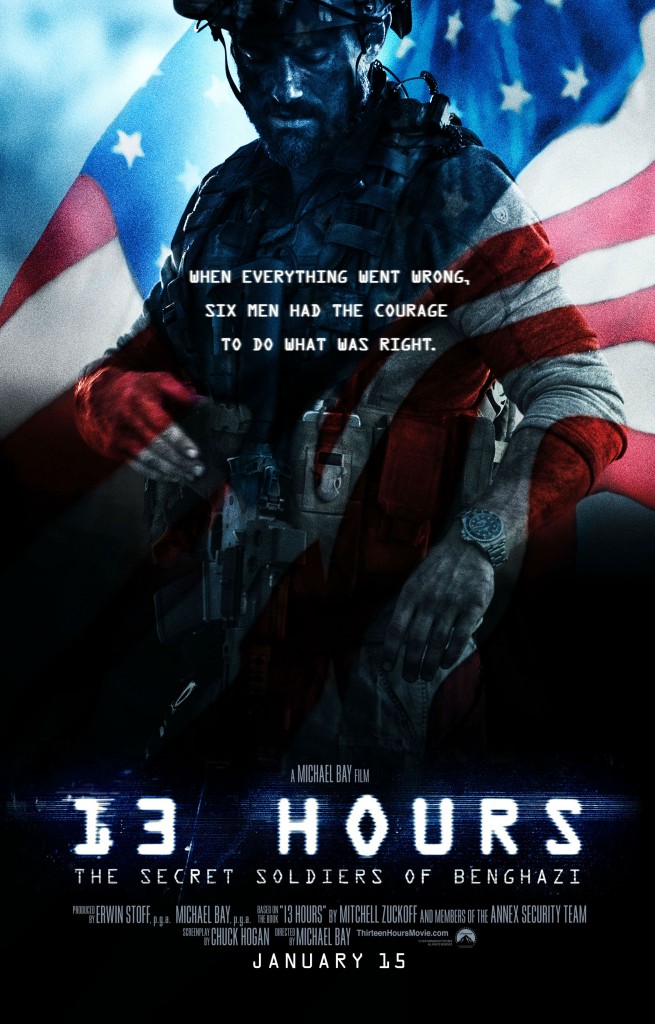

Movie Breakdown: 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers Of Benghazi (Noah)

Pre-Screening Stance:

I will say that I’m not opposed to Michael Bay expanding the spectrum of the types of films he chooses to direct. That said, the idea of Michael “Transformers” Bay taking on a real, historic tragedy like Benghazi seems a bit far-fetched.

Post-Screening Ramble:

To make a film about Benghazi correctly, you really have to make two different films. First, a historic military film, the type that uses the living truth, the facts as it may, to accurately tell a story about an event that has actually occurred. Second, you have to make a film that places an opinion of some kind on the situation at hand. This is difficult in the hands of even the most talented director, and few historical films manage to do either with any aplomb. Trouble is with 13 Hours is that by allowing Michael Bay to take the reins a third type of film is created – a Michael Bay film. The type of movie that has an obnoxious comic relief character (think Martin Lawrence in the Bad Boys films), that has clear good guys to root for and clear bad guys to shake your patriotic fist at, the type of film that isn’t mired in the confusion that our current war(s) in the Middle East are prone to. Which is why, ultimately, 13 Hours is a failure, another notch in the belt of Michael Bay’s blockbuster auteurism, but as a film that has anything to say about events in Benghazi in September of 2012, this film does not work. For those who haven’t read the news in the last five years, Benghazi was a small, classified outpost in Libya that in the aftermath of Gaddafi’s fall from power, became a microcosm of age-old conflicts, a tiny fissure of anger and hate that ended up killing a lot of people, including Ambassador Chris Stevens. Bay chooses to focus on six contract soldiers (lead by James Badge Dale’s Roan) who went against orders to protect those who were trapped in the Benghazi outpost as a mob of violent rebels overran it. A good film could be made about this subject as it illuminates many of the issues related to our near-constant military presence in the Middle East, but Bay hasn’t made that film. Instead, he’s chosen to make an action movie that uses the events to allow his six, burly soldiers (even John Krasinski is looking beefy in the film) to crack wise, be bad-ass, and talk, almost incessantly about their families at home. Though Bay manages to sidestep the film being offensive in its portrayal of the attack and counter-attack by blanketing the whole damn, lengthy affair (the film clocks in at almost two and half hours of military might) in a wash of patriotism and authentic military speak, showing an almost sycophantic respect for his six main characters and the arduous 13 hours they plodded through, guns blazing. But in the end it doesn’t matter because Michael Bay can’t stop being Michael Bay. He wants the credibility of a historical military film (no matter how recent that history might be) but he also wants his audience to have a good time, shed a few tears and walk away knee deep in love with the power of good old-fashioned American war. And so, instead of a powerful, poignant film like Zero Dark Thirty, we get an attractively shot action film (Bay still does violence real pretty) loosely garbed in the trappings of an actual event. We get wise-cracking interpreters, tough-but-sensitive soldiers, and a whole lot of shots of the American flag either waving poetically in the wind or drowning in the consequences of the horrible evening at Benghazi. It is, as much as it tries not to be, jingoistic fluff, rightly cannonballed into the doldrums of January.

One Last Thought:

I was worried when I walked into this film that Bay would let his cardboard characters and linear plot lend themselves to aggressively racist portrayals of the Libyans who attacked the outpost at Benghazi. He doesn’t, exactly, but instead does something much worse – he creates a scenario where no Libyan is onscreen without the support of ominous music, sweaty brows and tension ratcheted to the nines. Instead of exposing himself and his beliefs (whatever they may be) he allows his stereotypical portrayal of Libyans, and Middle Easterners in general, slip by as background noise, further clouding a subject that always, forever, needs a much defter explanation.