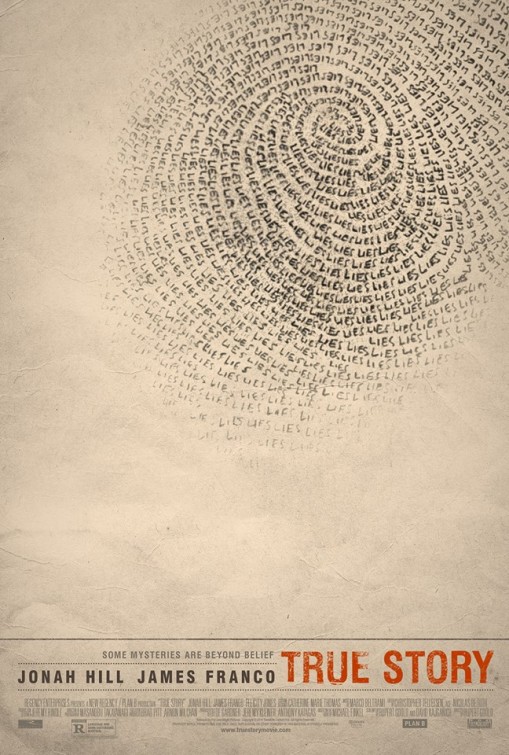

Movie Breakdown: True Story (Noah)

People are doing traditional-style reviews all over the web, so we decided to try something different. In each “breakdown” we’ll take a look at what a film’s marketing led us to believe, how the movie actually played, and then what we learned from it all. Read on!

The Impression:

I might be a little exhausted in terms of James Franco. I respect that the man is a prolific “artist” who wants to make as much “art” as possible, but I could do without his smug good looks and particularly abstract take on acting. That said, watching Jonah Hill’s slow progression into serious acting is always fun.

The Reality:

If you ever spend anytime with anyone who’s ever written anything, you’ll probably at some point be told to “show, not tell.” This means that instead of broadcasting to your audience the intentions and reasoning of your characters, you allow their actions and words to “show” this for you. True Story is a good film, a solid film one might say, but one that dances so precariously on the line of “show, don’t tell” that you have to wonder if director, Rupert Goold, managed to make an enjoyable film that seems more weighty than it actually is. Which in a film like True Story, could most certainly be the case. Based on a, sigh, true story, the film follows the life of former New York Times writer Mike Finkle (Jonah Hill) in the wake of being disgraced, and canned, for lying in an article. Stripped of his professional credibility, Finkle sequesters himself in his home in Montana and waits for something to happen. In Mexico, Christopher Luongo (James Franco), is fleeing police in the wake of his family being discovered murdered. And he’s using the alias Mike Finkle, of The New York Times. Luongo is caught, Finkle becomes interested in the case, and after visiting Luongo, becomes a willing participant in sharing the story of his life and, presumed innocence. The meat of the story revolves around a series of conversations the two men have, where Luongo sort of seduces Finkle into the idea of writing a book about him. Though both actors do good work in the film, there’s something about the interaction between the two that doesn’t sit right, as if the well known real life friendship heightens the sense that these two are acting. Or maybe, just maybe, Goold wanted to make these moments in the jail cell seem vaguely unrealistic, as if he was hinting at this idea that the “true story” that Finkle was writing never, to anyone observing from the outside at least, seemed real at all. Yet Goold never overtly states any of this. Yes, we watch as Finkle becomes, to some degree, a pawn to Luongo’s small machinations, and we see how important the story and the friendship becomes to a man wallowing in creative limbo, but Goold, to the film’s detriment, never pulls the camera far enough back to really showcase why it matters. Instead, we get a well made film (and Goold has a keen aesthetic eye and fine hand with his actors) that tells a story about a story, well, about a story, but in the end, that’s it. Sure, you can argue that Goold has made a film that challenges the audience to come to their own conclusions, or, you can look at it and see a director who couldn’t figure out how to address the central themes of his narrative, so he just hung it all out to dry and hoped everyone else could figure it out.

The Lesson:

Felicity Jones, who plays Finkle’s wife in the film, is going to be a massive star. She’s relegated to a sort of quiet, brooding-lay role in the film, but her one face-to-face interaction with James Franco is the highlight of the film. A twisty, brief conversation that exposes the truth at the heart of Luongo and gives the film that little oomph to really stick the landing.