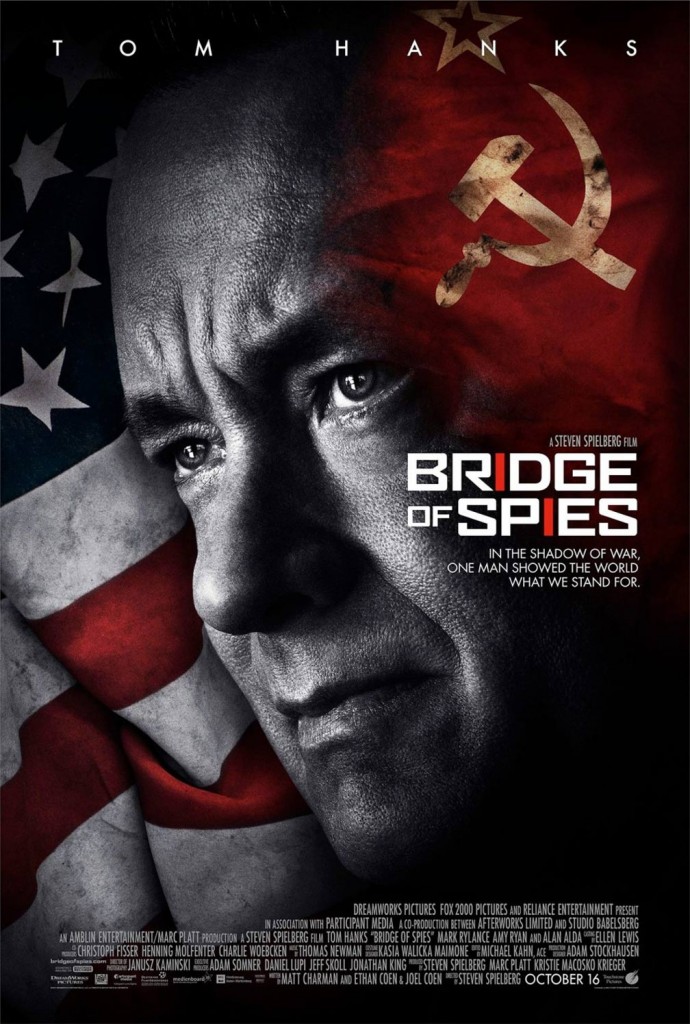

Movie Breakdown: Bridge Of Spies (Noah)

The Impression:

A new Steven Spielberg film is an event. I don’t care if he made the fourth Indiana Jones film and I don’t care if kids today want giant explosions and scantily clad women and rap music. Steven Spielberg is an American cinematic master and we will all grovel in his footsteps.

The Reality:

Steven Spielberg is, truly, the quintessential American master of cinema. Bridge of Spies isn’t proof of this, it’s just another argument in an ongoing case. Sure, the man hasn’t always made amazing films – Indiana Jones 4, I’m thinking of you – and even his great ones sometimes fall flat for me, but he makes movies that reflect a certain deep, knowledgeable faith in the goodness of people to do good upon other people. And he does so with such a firm grasp on the capabilities of film, that each and all of his films seem to be the still beating organs of the American body placed upon the screen. Bridge of Spies is very much this film. It stars Tom Hanks as real life attorney James B. Donovan, a lawyer-turned-negotiator for the United States government who defended convicted Russian spy Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance who should, if this performance is any measure of his skill, be in every film ever) and then helped to use him as a pawn in the negotiation for downed U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers. This is a fine film, a Cold War period piece steeped in dusty color palettes and the tension of a world just about tipped on its axis. But what Spielberg does best (with the help of Tom Hanks who plays Donovan as a good man, with just a touch of lawyer-y shmuck living within him) is to use a film ostensibly set within the fragile international politics of a post-WWII reality to reflect the inadequacies and potential saviors of our own time. Though Rudolph Abel is a spy for the Russians – he never denies this – Donovan is able to see past it, to see the shades of grey that exist between the stark black and white of government bureaucracy and mob mentality, to a place where, quite frankly, we all exist outside of the trappings of our more superficial descriptors. It isn’t always a perfect film – the jump from America to East Berlin that occurs halfway through the film is jarring and breaks the film’s languorous, masterly pace and like all Spielberg films do it goes on a little long – but when it ends and things are maybe going to be better in the world, you can’t help but thank Spielberg for being exactly who he is as a filmmaker. One who still believes that a small part of this world might just be worth fighting for.

The Lesson:

This is turning out to be a fine year of cinema.