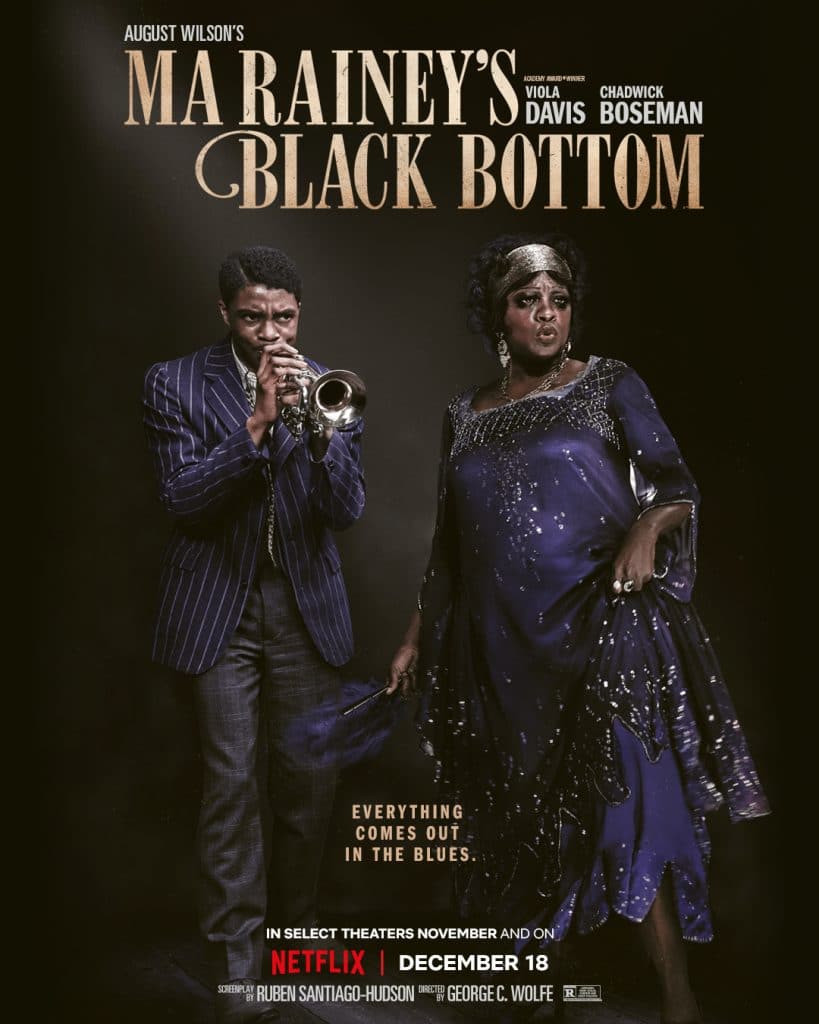

Movie Breakdown: Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (Noah)

Pre-Screening Stance:

August Wilson is an American master and his Pittsburgh Cycle is one of great feats of modern playwriting. Adaptations of plays can often times lounge in the static area of visual filmmaking but I will happily take the chance to see Viola Davis and Chadwick Boseman rip into the grade-A prime beef that is Wilson’s dialogue.

Post-Screening Ramble:

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is, without any real reservation, a play filmed for the screen. The film – the story, on the surface, of a Blues recording session in the 1920s – takes place in two rooms. The dialogue leans towards soul-searching monologue. The plot – scant at best – builds slowly, act-by-act, until it all comes crashing down. And yes, it can feel theatrical, claustrophobic even, but it does not suffer a bit for it. George C. Wolfe’s camera uses every ounce of space in a room, flitting from actor to actor, circling a star when they’re giving it their most, turning a one-room play into something that, frankly put, moves. But really all of it rests in the shadow of the two-performances that anchor and balance the film – Chadwick Boseman (in his last role) as Levee and Viola Davis as the titular Ma Rainey. Both are outstanding in the film, their presence on the screen enough to suck the air from a room. Boseman’s Levee is a talented cornet player who is mired in the pain and trauma of his own past, his trust of his fellow musicians eroded by his hopes of saving himself through his own pipe dreams. Boseman is so raw in the film, a swarm of bees enclosed in a skin suit, every jab or barb or failure slowly driving up his energy until the climax. It’s an incredible piece of acting and it really cements the loss of Boseman earlier this year. But, even with all the context, Viola Davis’ performance is the standout. Ma Rainey is a powerful, early diva of the Blues genre, powerful in her success but still dependent on the white man’s studio system she hated. She is demanding, bounces between emotional highs and lows, and is never far from snapping. Davis is amazing in this role, a feat of both emotion and physicality that shows just how powerful a Black musician could be in the era, but also how fragile that power was. Her cooly-desperate power grab paired with Boseman’s frantic hopes for the future show the minute and the widescreen spectrum of this small part of the Black experience in the 1920s. Even if Wolfe never shakes the feeling of a play completely, it doesn’t matter – this is a powerful piece of work regardless the genre.

One Last Thought:

Boseman’s Levee has a monologue where he’s screaming at God for abandoning him and knowing now that he was on the verge of dying makes it almost uncomfortably moving, as if Boseman himself is arguing with his maker.

One Other Last Thought:

I watched Draft Day after Ma Rainey’ Black Bottom (I have no reasoning for this choice) but to see Boseman there built like a football player and then in Ma Rainey, remarkably skinny – is both shocking and increasingly hard to believe that the actor was able to keep moving and keep giving performances like this when he was clearly so sick. What a fucking loss.