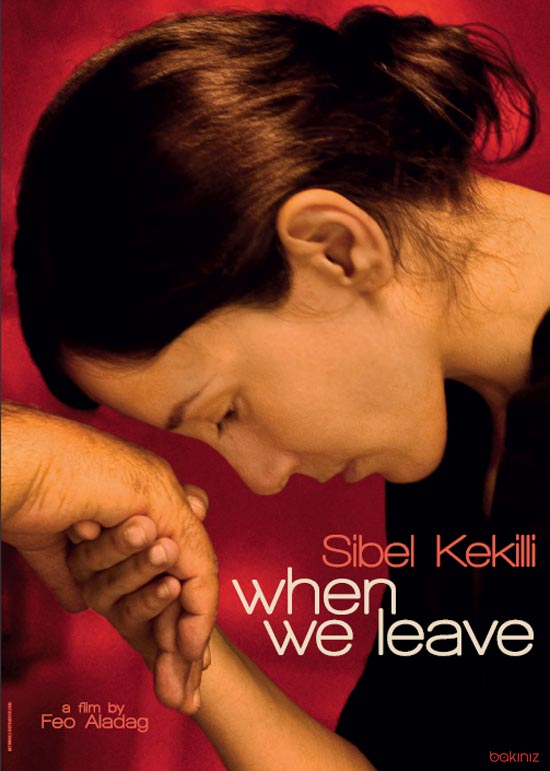

The path to free thought is a dire one in Feo Aladag’s debut feature When We Leave. Umay (Sibel Kekilli) is a 25-year old woman, married with child who lives with an abusive, ex-soldier husband within a tightly reigned Muslim community. After a particularly brutal meal (Aladag uses the dining table and the communal dinner as a dangerous weapon in When We Leave) Umay takes her young son Cem and flees to her parent’s home in Berlin. Yet, the home is not where the heart is, and the free-spirited young woman finds no solace in the arms of her parents, equally conservative Muslims who have no time or understanding for a woman living alone with child. Aladag drags her main character through the mud, addressing the the constricting familial ties that bond so many close-knit religious communities along way. Never once during film though does Aladag resort to portraying her characters as one-not villains, or untouchable Madonnas. The characters of When We Leave react as their world dictates, with sadness and yearning and the slow pull backwards of the unyielding brick of religious law.

When We

Leave is a fantastic portrayal of the conservative world

of Muslim relations, one that shines a bright light on the

archaic relations between man and woman without ever placing

a judgement on them. Umay leaves her family because she no

longer wants to be beaten, no longer wants to be held back

from walking the path she’s keen to walk. She’s 25, with a

child, and no longer wants to be beaten by her husband, her

brothers, at time her fathers. Her leaving though isn’t

without consequence, it destroys the family’s honor, and

quietly cripples their standing in the community. To Umay,

stepping away from her family is a tragedy as well, and in

scene after scene, with a nauseating knot of tension, she

returns to her family, never giving up hope that she, as she

wants to be, will be once again accepted in to the fold.

Though Umay is clearly the character we are meant to

emphasize with, Aladag never lets her off easy. She is

irresponsible and passionate to the point of losing site of

her son’s best interest, but she’s reacting the only way she

knows how. The way her family has taught her. The film,

stark and quiet, isn’t about how terrible the crushing

confines of conservative religion can be (though it

certainly addresses this) but the ties that bond us. The at

times unbreakable connections between our blood-relatives

that pull us back over and over again, regardless of what

they put us through.

|