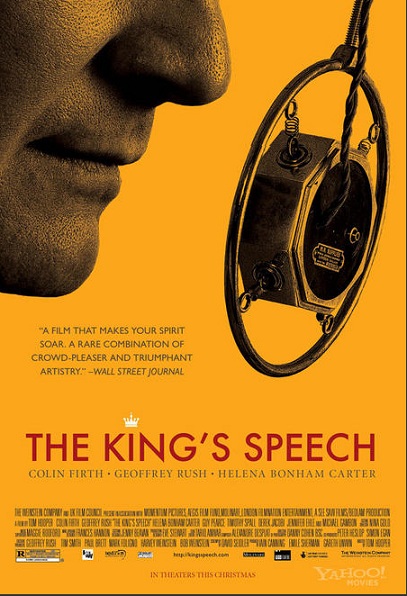

Unfairly, walking in to Tom Hopperís The Kingís Speech, I expected to hate it. Immensely. In my mind, it seems just the sort of Hollywood (British or not) fare that gains traction post-festival season, and is ballooned to the top by a charmingly silly, yet bottom-line serious, take on a historical event or an historical figure. In the case of The Kingís Speech King George VIís (Colin Firth) vehement stutter and the relationship it helped to foster between Bertie (King Georgeís childhood nickname) and Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush), a talented though unorthodox speech therapist. Sounds like a quirky set-up with a great cast but in the end, it just sounds like Oscar bait hub-bub. The kind of dime-a-dozen period pieces that always clog the projectors this time of the year, the same kind that I go out of my way to avoid. Yet, because of its talented cast and burgeoning directorial talent in Tom Hopper, The Kingís Speech rises above the usual Christmas-time dreck.

Iíll say this

quite frankly, The Kingís Speech is exactly the film

the trailers make it out to be. Itís a film about an

unexpected relationship and the way it deeply affects both

the life and rule of a man who never wanted to be king. King

George VI has a bad stutter and it makes him seem less

dependable as a ruling figure. When his father dies (Michael

Gambon, shortly but impressively) and his daft,

American-loving brother (Guy Pierce) attempts to marry a

divorced woman, the potential for kingship becomes

inevitable, and Georgie must deal come to terms with his

debilitating stutter. It could be a childrenís book, a

simple parable about differences and how we address them,

but instead because of a finely written script and two

outstanding performances by Firth and Rush, it becomes a

keen character study. Firth plays Bertie as a child who was

never given the chance to grow up. A man trapped within the

stuffy, tight parameters of a royalty, who has been

eviscerated by the daunting insecurities passed along to

him. In Rushís Lionel Logue he finds not only a man able to

stand up to the all-encompassing wall of royal pressure, but

someone who he feels comfortable with. A "friend" unlike any

he has ever had. And the film thrives when these two actors

are on screen together. The moments where Logue attempts to

break down Bertieís stutter are enjoyable in a silly way,

and beautifully (as the entire film is) portrayed by Hopper.

When the two men are separate, the filmís formulaic script

(we all know that Bertie becomes king and that his speech

turns out just fine) bubbles to the surface, and though itís

still enjoyable it doesnít have the sparkle the other scenes

downright gleam with.

|